How Hillcrest Became One of San Diego’s Most Enduring Arts Districts

By Patric Stillman

If you know where to look, Hillcrest has been telling its artistic story for more than seventy years.

Sometimes it’s loud like a mural splashed across an alley wall. Sometimes it’s quiet like fossils embedded in the sidewalk, waiting for you to notice. Taken together, Hillcrest reveals itself as something rare. It’s a neighborhood where art didn’t arrive as a trend or a marketing strategy but as a way of life.

Long before Hillcrest was officially recognized as an LGBTQ+ Cultural District, it was already functioning as one. As Hillcrest historian Eleanore Meadows noted in a 1994 CBS News feature, artists began moving into the neighborhood as early as the 1950s. That early creative migration laid the groundwork that continues to support Hillcrest’s cultural spirit today.

In the postwar years, Hillcrest became fertile ground for artists, designers, and creatives drawn by affordable spaces and a sense of possibility. Modernist cinemas, design studios, and neighborhood theaters signaled that Hillcrest was open to new ideas. Art wasn’t confined to elite venues. It lived alongside everyday life.

Beginning in the 1950s, the neighborhood attracted architects, interior designers, and visual thinkers drawn by proximity to Balboa Park and a community open to experimentation. Along University Avenue, Park Boulevard, and Fifth Avenue, independent interior design studios, lighting and furniture showrooms, upholstery shops, architectural offices, and graphic studios clustered organically. Together, they formed an unofficial design district. A walkable creative corridor where modern taste helped shape the city’s visual direction.

At the heart of this ecosystem was the Hillcrest Design Center, founded in 1950 (now Futuro Space across the street from The Loft). More than a showroom, it functioned as a collaborative environment. A shared campus for designers, architects and artists working across disciplines. Ideas moved freely here, influencing everything from residential interiors to commercial spaces throughout San Diego. The Hillcrest Design Center was part of a broader network of small studios and creative businesses that gave Hillcrest its identity as a place where aesthetics mattered.

Even Hillcrest’s mid-century cinemas reflected this design-forward mindset. Modernist theaters like the Capri (now The Egyptian condos) were carefully crafted environments, where you could see an “ultra modern” bronze sculpture hanging from the 17’ lobby ceiling and Miro-inspired mosaics in the bathrooms. Its owner curated art exhibits in the lobby featuring San Diego artists William Munson, Fred Hocks, Sheldon Kirby, Linda Lewis, and Fred Holle.

As the decades progressed, Hillcrest’s growing LGBTQ+ community brought with it an even deeper relationship to creative expression. When traditional institutions weren’t always welcoming, the community built its own stages.

One of the clearest examples of this transformation is The Rail, a name that carries far more history than many realize. Originally opened in the 1930s inside downtown’s historic Orpheum Theatre building, The Brass Rail was steeped in theatrical DNA from the start. In 1958, it became a predominantly gay piano bar, and in 1963, it relocated to Hillcrest, bringing that performance legacy with it.

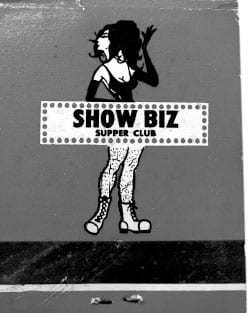

By the 1970s, Hillcrest was home to the Show Biz Supper Club (now Baja Betty’s), widely recognized as San Diego’s first dedicated drag club. More than nightlife, Show Biz offered a formal stage for drag at a time when few such spaces existed. Performers developed full numbers complete with choreography, costuming, and narrative, establishing drag as a respected and enduring art form within the neighborhood that entertained locals as well as Hollywood celebrities.

Together, venues like The Rail and Show Biz Supper Club helped cement Hillcrest as a place where queer performance could flourish openly. Drag functioned as an enduring art form, shaping Hillcrest’s visual culture, performance traditions and sense of creative possibility over decades.

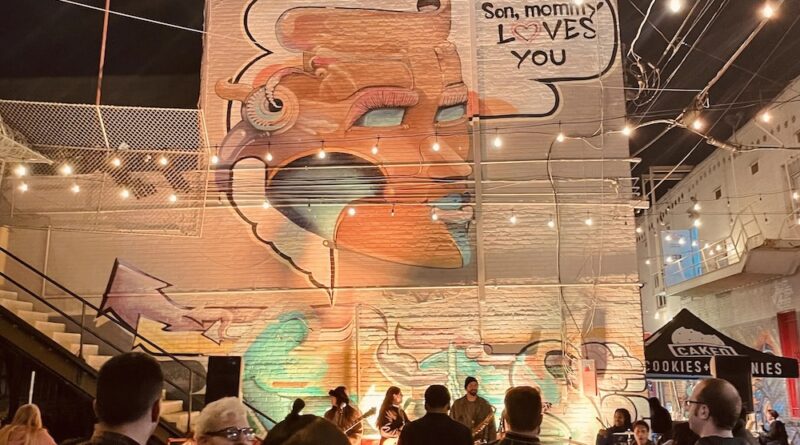

As Hillcrest moved into the 21st century, its artistic voice expanded outdoors. Walls became canvases. Alleys became destinations.

In 1998, artist Doron Rosenthal was commissioned to install Fossil Exposed, the neighborhood’s first public art project. Embedded in the sidewalks are circular granite markers that can still be seen today. With 150 fossil markers placed throughout the area, the work reminds passersby that in Hillcrest, art often reveals itself quietly, once you slow down enough to see it.

A pivotal moment came when Shepard Fairey painted Viva la Revolución mural titled Hillcrest, Obey Eye in 2010 which was on the side of Urban Outfitters (Now Snooze). It sent a clear message that these walls mattered. Artists noticed. Neighbors noticed. Soon, brushes came out across Hillcrest.

Today, there are more than 25 murals throughout the neighborhood, along with a utility box art program and countless interior murals inside local businesses. Together, they form a living, breathing gallery connecting residents, visitors and small businesses through a shared visual language.

At the center of Hillcrest’s contemporary visual arts ecosystem is a trinity of creativity formed by The Studio Door, ArtReach San Diego, and Revision San Diego. While each operates differently, they are united by a belief that art should be visible, accessible and woven into the neighborhood rather than confined to traditional institutions.

All three prioritize process as much as presentation. Artists work in public, invite dialogue and create in relationship with the community around them. Whether through studio practice, youth education or large-scale public murals, each treat art as a living exchange rather than a finished product. A shared commitment to equity and inclusion expands who gets to see themselves reflected in public space, reinforcing Hillcrest’s long-standing tradition of turning ordinary places into cultural touchstones.

Looking ahead, Hillcrest’s artistic legacy is extending into the public realm through the development of Pride Plaza and the Pride Promenade along Normal Street. Shaped by years of community input, the project reimagines streets and gathering spaces as places for reflection, celebration, and public art. Planned features include interactive artworks, permanent sculptures and a striking community-scaled mosaic at the base of the Pride flag ensuring the space reflects the voices and creativity of the neighborhood itself.

Hillcrest isn’t an arts district because someone declared it one. It’s an arts district because artists kept showing up, because performers built stages where none existed, murals spoke when voices were silenced and creativity became inseparable from survival, joy, and pride. Hillcrest is more than a neighborhood; it is a gallery. And every wall, stage, sidewalk, and story continues to tell us the story of San Diego’s most enduring neighborhood arts district.