Gallery of the Damned: Art in the the World of Film Noir

By Patric Stillman

Step into the gallery of shadows. Imagine a world where the lights are low, the faces mysterious, and every painting might be a clue to something darker. This is the world of Film Noir—a style of movie from the 1940s and 1950s where crime, mystery, and art all come together in unexpected ways.

You might know Film Noir for its private detectives in trench coats or smoky lounges filled with secrets. But what many do not realize is how much art plays a role in these stories. At a time when the world was recovering from war and trying to understand a fast-changing future, movies and modern art started speaking the same dark, emotional language.

Back then, new ideas in psychology were shaking things up. Thinkers like Sigmund Freud and Carl Gustav Jung were helping people explore dreams, fears, and the unconscious mind. At the same time, artists like Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Salvador Dalí were creating wild, emotional, and abstract paintings that did not look like anything people had seen before. And these ideas did not stay in galleries—they made their way into movies.

Some of the filmmakers behind Film Noir came from Europe, bringing with them the moody, shadowy look of German Expressionism. Directors like Fritz Lang, who fled Nazi Germany, helped shape American Noir movies with their bold, emotional visual style. Soon, stories about crime and obsession started featuring not just alleyways and jazz clubs, but also art galleries, artists’ studios, and mysterious paintings.

Art was not just decoration in these movies—it was part of the mystery. Sometimes, a painting sparked an obsession. Other times, a sculpture hinted at a character’s inner world. These works added a whole new layer to the drama.

In two Film Noir classics, Laura (1944) and Fritz Lang’s The Woman in the Window (1944), a portrait of a beautiful woman sets the story in motion. The portrait in Laura looks like a painting, but it’s actually a photograph by Frank Powolny, brushed with paint to seem like a real canvas. There was an original painting of Laura created by Hollywood portrait artist Azadia Newman that was scrapped before filming started. Meanwhile, the painting in The Woman in the Window featured a paintingby Paul Clemens, a rising American artist, that played a key role in building the movie’s mood.

Sadly, many of the artists who created these works for film were never credited. Albert D’Agostino, RKO’s legendary art director, orchestrated entire museums’ worth of fake paintings for films like Crack-Up (1946), drawing on a team of illustrators, painters, and set designers whose names have been lost to time.

Sadly, the fate of cinematic art often mirrors the tragic stories it helps tell. In the case of the 1970’s television series Night Gallery, an artistic follow up to Rod Serling’s more famous Twilight Zone, the loss is strikingly sad. Each episode was introduced by a chilling painting, most created by artist Jaroslav “Jerry” Gebr, setting the eerie tone for what followed. Despite their importance to the series’ identity, many of these artworks were later discarded or painted over. Like the artworks of the Noir period, only a handful survive, rescued by dedicated collectors and fans.

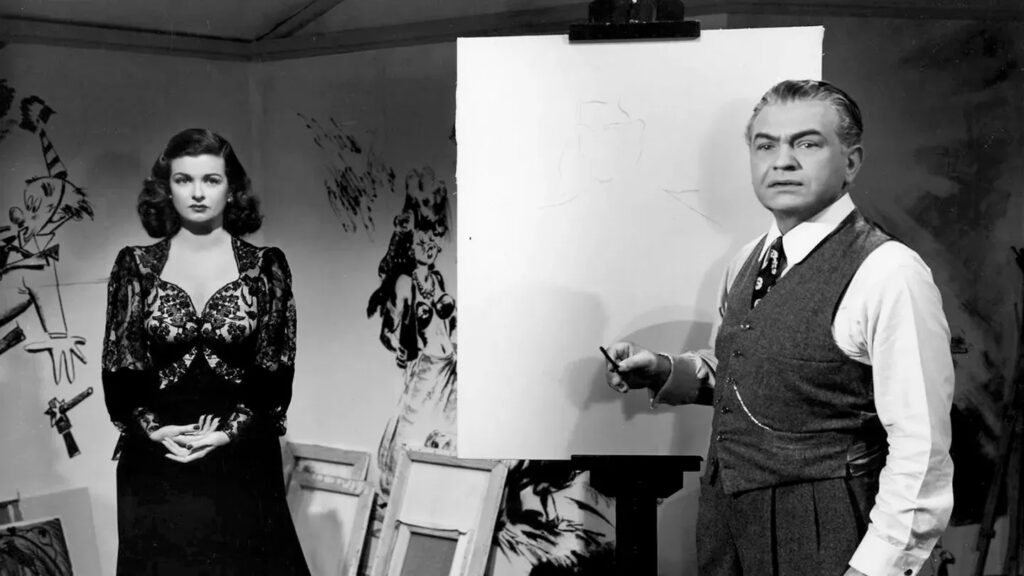

One movie where the artwork took center stage is Scarlet Street (1945), another Fritz Lang film. Edward G. Robinson plays a lonely man who paints in his spare time, only to have his art stolen and sold under someone else’s name. The real paintings in the film were created by John Decker, a well-known Hollywood artist at the time. His work captured the raw emotion of Robinson’s character so well that the paintings were even shown at the Museum of Modern Art in New York after the film came out.

Some Noir films had fun with how people saw modern art. In Crack-Up, for example, there’s a scene where curator berates the artist behind a strange painting that looks like a Salvador Dalí while the public laugh. That same year, Dark Corner (1946) includes two beat cops humorously try to make heads and tails out of a sculpture. This reflects how, at the time, many people did not understand or trust modern art. Still, these movies used bold and abstract images to show what their characters were feeling deep inside.

Even in the later years of Noir, the artist’s studio remained a dramatic setting. In Born to Be Bad (1950), Joan Fontaine plays a schemer who becomes the muse of a painter, with real artwork by modernist Ernst Van Leyden, who hung out with Pablo Picasso and Willem de Kooning. In Blue Gardenia (1953), Raymond Burr plays a sleazy pin-up artist whose studio is filled with glamour art inspired by men’s magazines like Playboy, which was launched the same year.

So much of Film Noir is about looking beneath the surface. That’s why art fits in so perfectly. Whether it’s a painting that hides a lie, a gallery full of secrets, or a portrait that draws someone into danger, art adds a deeper level of meaning to the stories.

If you’ve never looked at these American classics with art in mind, this is a great chance to start. Since most of these films are in the public domain, you can find them on YouTube and streaming on classic film channels. Step into the world of Film Noir, and let the art guide you through the shadows. You might be surprised by what you find.

From April 3 to 25, 2025, The Studio Door brings the cinematic shadows of Art Noir to life in a curated exhibition that mirrors the intrigue explored on screen. Artists use shadows, bold contrasts, and dramatic scenes to explore secrets, tension, and the unknown—inviting you to step into a world where nothing is quite what it seems.

Essential ART NOIR Viewing

The Woman in the Window (1944) – Joan Bennett (Hollywood Chameleon turned Noir Goddess) as a sophisticated femme fatale with impeccable style.

Laura (1944) – Essential noir with Clifton Webb (Hollywood actor who lived with an “open secret”) in peak camp form—yes, that bathtub scene lives up to the legend.

Phantom Lady (1944) – No-nonsense Ella Raines flips the script in noir drag, owning the room in a smoky jazz club during a drum solo scene loaded with steamy, subtextual heat.

Scarlet Street (1945) – Joan Bennett returns as a seductive con artist opposite shirtless, bad-boy Dan Duryea in his first major noir role.

The Dark Corner (1946) – Clifton Webb returns with Lucille Ball (I Love Lucy) in one of her best dramatic performances—witty, sharp, and surprisingly tough.

Crack-Up (1946) – Paranoia and forgeries take center stage in a suspenseful museum mystery, with a cheeky nod to how baffling modern art seemed to the general public at the time.

The Second Woman (1950) – Robert Young (Father Knows Best) broods in a stunning mid-century modern home perched on the cliffs of Carmel.

Born to Be Bad (1950) – Joan Fontaine (Rebecca, Suspicion) at her most devious, scheming through glamorous San Francisco in full camp mode.

Blue Gardenia (1953) – Raymond Burr (Perry Mason) plays a predatory pin-up artist opposite an emotionally vulnerable Anne Baxter (All About Eve) with a haunting torch song by Nat King Cole.