Blueprint for Resistance: Karibu and AAGWA’s Organizing Legacy

By Gabrielle Garcia and Nicole Verdes

For Black History Month, we’re illuminating the powerful history of two organizations led by queer Black folks in San Diego through materials from our collection that reveal not just their story, but the organizing strategies and coalition-building work that made their impact possible—Karibu and the Afrikan American Gay Women’s Association. These archival materials document the “how” of their activism: the meetings convened, the alliances forged, the resources mobilized, and the community networks built to create lasting change.

These items are made publicly available, as are many other stories and collections, through our online archival collections (https://lambdaarchives.starter1ua.preservica.com/). It bears repeating that we are living through a moment of aggressive and deliberate historical erasure. When our history is freely accessible and thoroughly documented—when we preserve not just the victories but the blueprints for achieving them—we build collective memory that’s harder to erase, more difficult to deny, and impossible to silence completely. By sharing the tactical and relational work behind these movements, we ensure future organizers have the roadmap and inspiration to continue this vital work.

Karibu

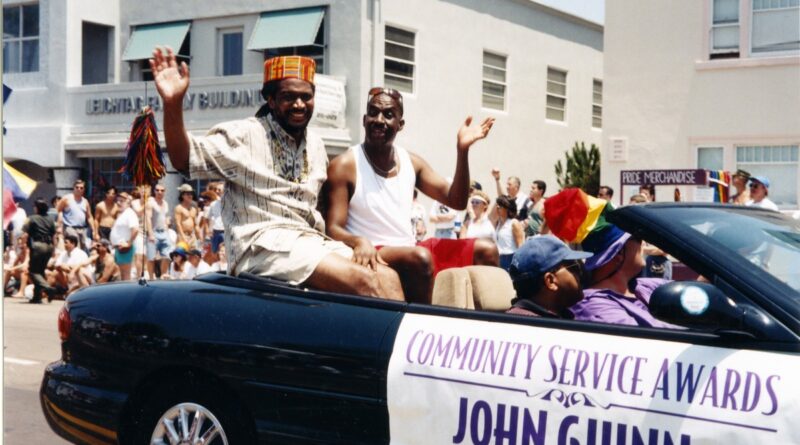

Karibu, which means ‘welcome’ or ‘enter’ in Swahili, was founded in 1995 by John Guinn, Kenneth Coleman, Joseph McCombs, Pete Simms and Ric Williams through a deliberate organizing strategy that built on lessons from LAGADU (Lesbian and Gays of African Descent United), which had dissolved between 1992 and 1994, partially due to the passing of founder and leader Marty Mackey.

The founders strategically structured their approach around multi-layered service delivery and community capacity building. Originally centering services for African-American gay, bisexual, and transgender men (who have sex with men) affected by HIV/AIDS, the organization intentionally expanded its scope to HIV/AIDS education and risk reduction programs and related support services to people of color once they felt they had achieved their original mission of “making more African-American men aware of the dangers and preventative actions surrounding HIV and AIDS and making treatment more accessible.” While the organization focused its support for people of color, people of any race or background were welcomed and served—a coalition-building approach that strengthened community ties.

The infrastructure they built:

- Weekly peer support meetings every Wednesday created consistent community touchpoints

- The Community Action Team provided rapid response to emerging needs

- The Companion Advocate System created a peer-to-peer support network that distributed care labor across the community

The programs they sustained: African American Men’s Support Groups, Men’s Intimacy Groups, Swahili Courses, Arts and Crafts classes, and Volunteer and Peer Advocate trainings that built skills and leadership capacity within the community.

The partnerships they leveraged: Early in its existence, Karibu secured fiscal sponsorship first from the San Diego Urban League and then The LGBT Community Center before achieving independent 501(c)3 status—a strategic pathway that provided organizational stability while building administrative capacity. Additionally, Karibu secured Ryan White Care Act funding beginning in 1998, ensuring sustainable program support.

The Karibu Center operated from 3960 Park Blvd., San Diego, with John Guinn serving as executive director. The organization’s success depended on distributed leadership and specialized roles: Jimmy Lovett Jr., Kevin Johnson, Kenneth Coleman, Joseph McCombs, Charles Beasley (who started the Party in the Park series), Norman Jackson, Clarence Holeman (program coordinator director and Party in the Park co-chair), Robert Carter (HIV Prevention Coordinator), Pete Sims, Milton Webb (companion advocate and volunteer), Dr. Fred Vanhoose (program coordinator), Harold Cooks (Outreach Educator), and Ramon Murray (Technology Support Specialist)—each contributing specific expertise to build a resilient, community-responsive organization.

Afrikan American Gay Women’s Association

The Afrikan American Gay Women’s Association (AAGWA) was founded in 1993 through intentional organizing that addressed a critical gap: African American women have historically been, and still are, one of the most underrepresented groups in society and the LGBTQ+ community. The organization was established as a social, support, and “political space where Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender African American women could gather to practice self-love, self-respect, and empowerment”, with a mission focused on “the elimination of prejudice and discrimination within the Gay and Lesbian African American community.”

Cultural organizing as political work: Co-founder Cheryl Bradford described AAGWA as a meeting place where African American women could “[share] everyday experiences, political concerns, and community ideas with women in similar situations.” The organization transformed this vision into concrete programming through extensive Black LGBTQ film programming that centered representation, education, and community dialogue.

The coalition model they built: Starting in 1996, AAGWA partnered with the Lesbian and Gay Historical Society of San Diego (Lambda Archives of San Diego today) and Karibu (African American gay, bisexual, and transgender HIV support organization) to present the first Marlon Riggs Film Festival at Diversionary Theatre. They screened “Black Is… Black Ain’t” (1994) and “Anthem” (1991) and featured special exhibits at Lambda Archives—creating multi-organizational events that pooled resources, audiences, and institutional knowledge.

Sustained cultural programming: AAGWA organized their first women’s history month film festival in 1997. At their second film festival in 1998, they screened “The Potluck and the Passion” (dir. Cheryl Dunye, 1993), “Bird in the Hand” (dir. Catherine Gund, Melanie Nelson, 1992), “Maya” (dir. Catherine Benedek, 1992), and “Badass Super Momma” (dir. Etang Inyang, 1996) at The LGBT Community Center. These film selections reveal their organizing philosophy: by centering indie, women-directed films about Black, and Latina, AAGWA used cultural programming as a tool to challenge dominant narratives, build cross-racial solidarity, and create space for stories that commercial venues ignored.

Organizing within a larger ecosystem: In a 1996 article, Cheryl Bradford noted, “[AAGWA] is the first African American women’s organization that is Lesbian or Gay.” Within a larger trajectory of Black/African-American LGBTQ organizations in San Diego, AAGWA emerged alongside Friends Unlimited, Karibu, World Beats Center, Spectrum, Shades of Color, Project Unity, and the Imani Worship Center after the dissolution of Lesbians and Gays of African Descent United (LAGADU) following founder M. “Marti” Corrinne Mackey’s passing in 1992.

The strategic shift toward specificity: The move from an all-gender Black LGBTQ organization with LAGADU to gender-specific groups—AAGWA and Karibu (HIV/AIDS support group for Black Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender men)—reflects an organizing evolution: the recognition that support and services addressing the unique needs and experiences of Black LGBTQ women and GBTQ men specifically could be more effective than an all-gender structure. After AAGWA’s disbandment sometime in 2000, the emergence of Black LGBTQ organizations such as Ebony Pride shifted back to an all-gender emphasis. This oscillation between centralization and decentralization as it pertains to intersections of Blackness and LGBTQ identity represents an ongoing organizing experiment, with each approach offering different strengths and weaknesses in structure and dynamic between community members.

Cross-movement coalition building: While community members’ needs and wants evolved, a consistent organizing principle remained: solidarity and connection to other local organizations, especially Black, Indigenous, POC-led groups. AAGWA’s collaborations with Karibu, Nations of the Four Directions, Daraja, APICAP, Glow, Imani Worship Center, Spectrum, and others followed a lineage of BIPOC networks of support and solidarity—networks formed strategically to counteract the racist hostility and harm that white LGBTQ spaces harbored and the homophobia and transphobia in some Black-specific spaces. This cross-organizational work created a third space where multiply-marginalized communities could build power together.

Why This History Matters Now

The organizing work of Karibu and AAGWA offers more than historical record—it provides a blueprint for survival and resistance in our current moment. Their strategies remind us that sustainable movements require infrastructure, not just inspiration: consistent meeting spaces, peer-to-peer support systems, cross-organizational partnerships, and cultural programming that educates while it empowers.

As we face renewed attacks on LGBTQ+ communities, particularly transgender people and queer people of color, and as we witness the systematic erasure of diverse histories from schools and libraries, these archives become both shields and swords. They document what’s possible when marginalized communities refuse to wait for mainstream institutions to recognize their humanity. They show us that organizing across differences—building coalitions between gender-specific groups, partnering across racial lines, creating third spaces outside both white LGBTQ+ organizations and heteronormative Black spaces—isn’t just idealistic, it’s strategic.

Karibu and AAGWA didn’t just create services and events. They built ecosystems of care, developed leadership pipelines, secured sustainable funding, and established networks of solidarity that outlasted any single organization. When we study their efforts, we inherit their tactical knowledge: how to leverage fiscal sponsorships, how to use cultural programming as political education, how to create peer advocacy systems that distribute care labor, how to name ourselves in ways that build rather than exclude.

This is the history they tried to erase. This is the blueprint they don’t want us to have. By making these materials freely accessible, we ensure that future organizers—facing challenges we can’t yet imagine—will know they’re not starting from scratch. They’ll know their people built movements before, and they’ll have the roadmap to build them again.